Contents

Here, the physical relationships between air pressure, temperature and altitude are systematically presented. It also examines whether greenhouse gases play a role in the climate system, including their chemical properties and the historical development of the greenhouse gas hypothesis.

First, however, we will focus on the physical fundamentals and begin by addressing the question of how air pressure is created. The answer to this question also resolves the question of temperature.

How is air pressure created?

As already explained on the "Atmosphere" page, the atmosphere consists of various gases that are bound to the planet by Earth’s gravitational pull. Without this force, the gases would escape into space, which in fact happens to a very small extent via the exosphere.

Gases are compressible and obey the physical laws of gases. In a gas mixture at constant pressure, each gas occupies the entire available space (entropy.

Thought experiment:

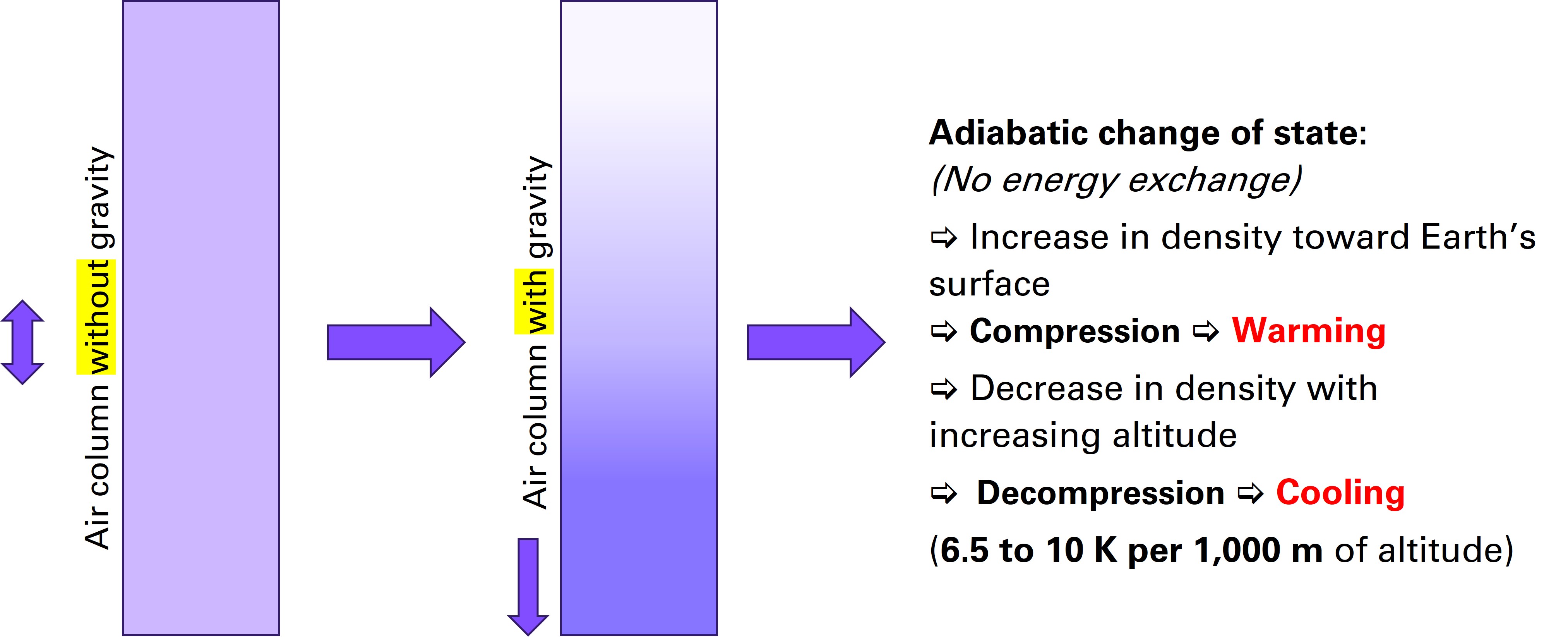

If the atmosphere were not attractedto Earth by gravity, the gases within the atmospheric volume would be evenly distributed and would have the same pressure and temperature everywhere. This situation corresponds to the left air column shown in the image, which represents the case without gravitational influence.

Relationship between altitude, air pressure and gravity |

In reality, all gases are pulled toward the Earth by the force of gravity acting on them (right air column). Assuming that no heat energy is added or removed (adiabatic change of state), the air is compressed near the ground, increasing its density; at higher altitudes, it expands and its density decreases accordingly.

These changes of state lead directly to a rise in temperature in regions of compression and to cooling in regions of expansion. They occur independently of the respective initial temperature. The vertical temperature and pressure gradients are thus direct consequences of fundamental physical processes.

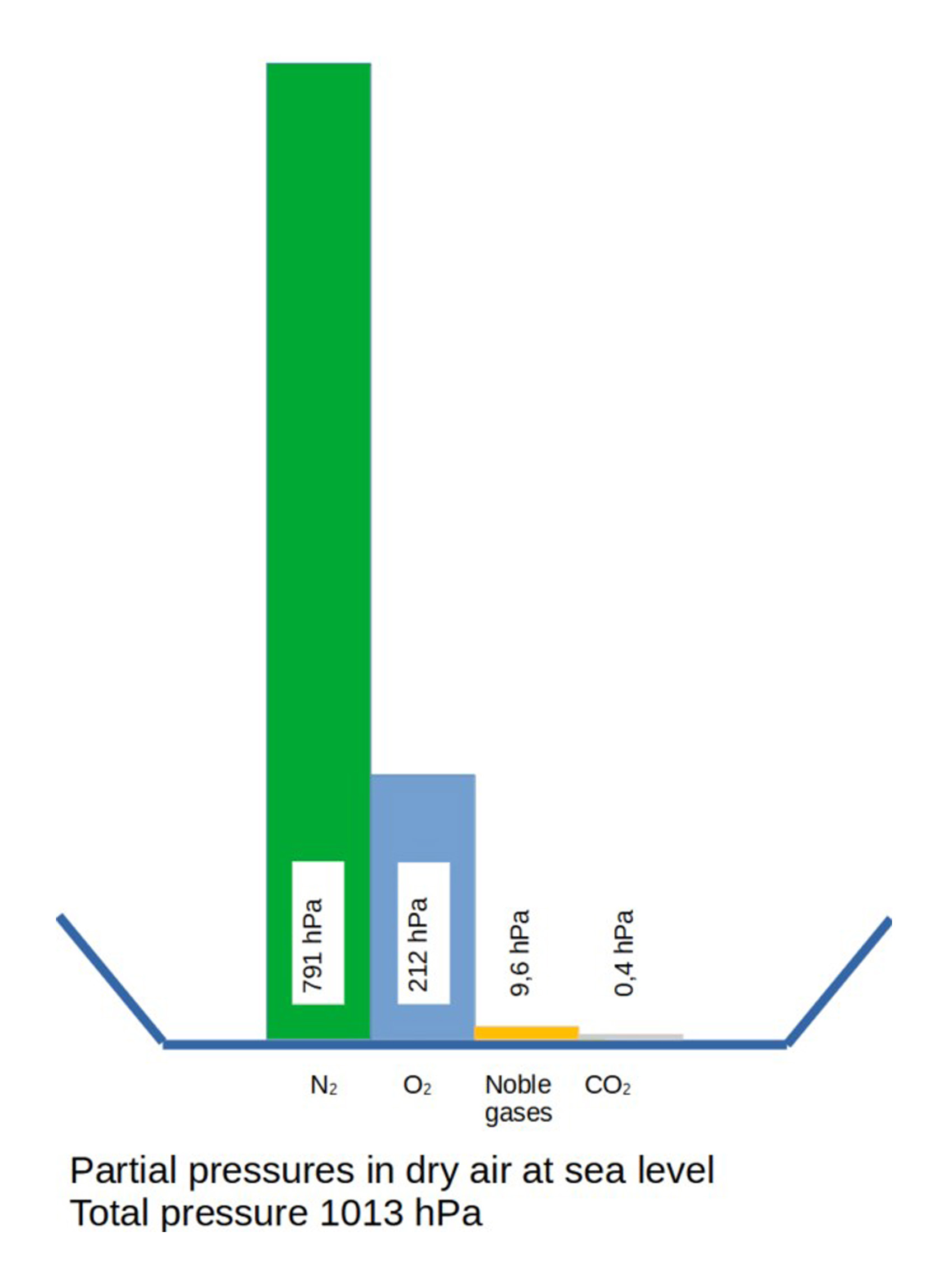

The gases in the air create air pressure through the sum of their respective weights (more precisely, the sum of their partial pressures), as shown in the following image.

© Brugger, 2023

A fruit bowl containing, for example, five apples, two pears, one strawberry, and one grape has a certain total weight on the scales. The same applies to air: instead of different types of fruit, it is composed of different gases, whose proportions together make up the total weight or, via their partial pressures, the total pressure.

The average air pressure at sea level is p0 = 1,013 hPa (hectopascals). This corresponds to a pressure of approximately 10,000 kg/m², or the weight of a 10-meter-high column of water over an area of 1 m × 1 m.

In everyday life, we are usually not aware of this pressure. If the air neither moved nor warmed up, but remained static at the Earth’s surface, the air pressure at sea level would be nearly constant. As altitude increases, however, the pressure decreases, as we know from driving in mountainous regions. We also know from experience in the mountains that the air becomes thinner with increasing altitude. The relationship between altitude and air pressure is described by the barometric altitude formula:

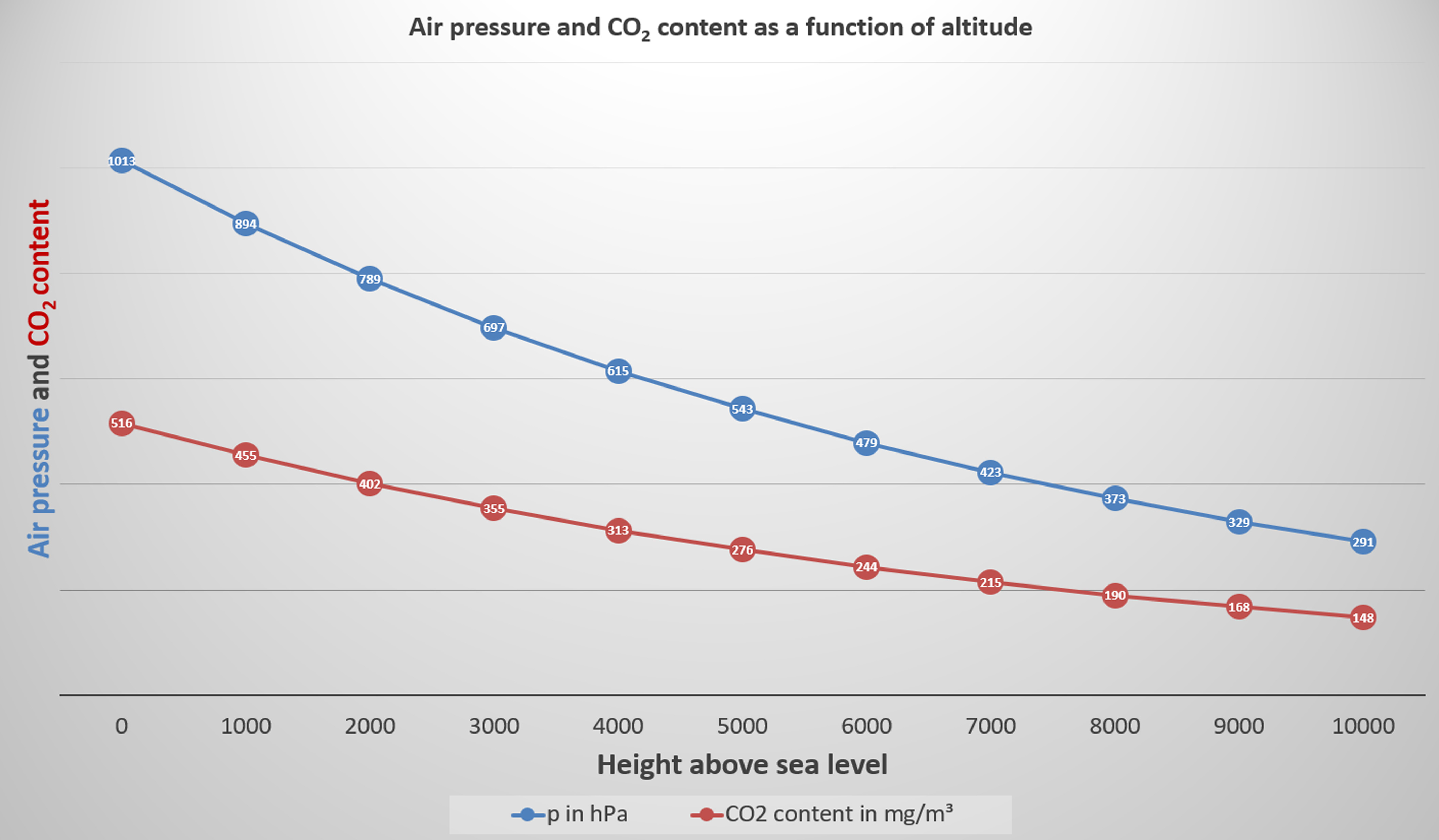

By applying the formula, the corresponding air pressure can be calculated for each altitude and represented graphically. The following graph does not take water vapor into account, as its proportion varies greatly in space and time, unlike the other gases.

Air pressure and CO2 content depending on altitude: |

Why does the temperature change with altitude?

At an altitude of around 5,400 meters, the air pressure has already dropped to about half of its sea-level value. This means that approximately 50 % of the total air mass lies below this altitude, while the remaining 50 % is distributed above it.

The reduced amount of oxygen is clearly noticeable when breathing, especially during physically strenuous activities such as mountain tours. To absorb the same amount of oxygen, approximately twice as much air must be inhaled at this altitude. The consequences are shortness of breath and an increased respiratory rate.

The cooling of the air with increasing altitude is due to the decreasing air density: as altitude increases, the number of energetically excited particles decreases, resulting in a lower temperature.

Radiation temperature of the Earth

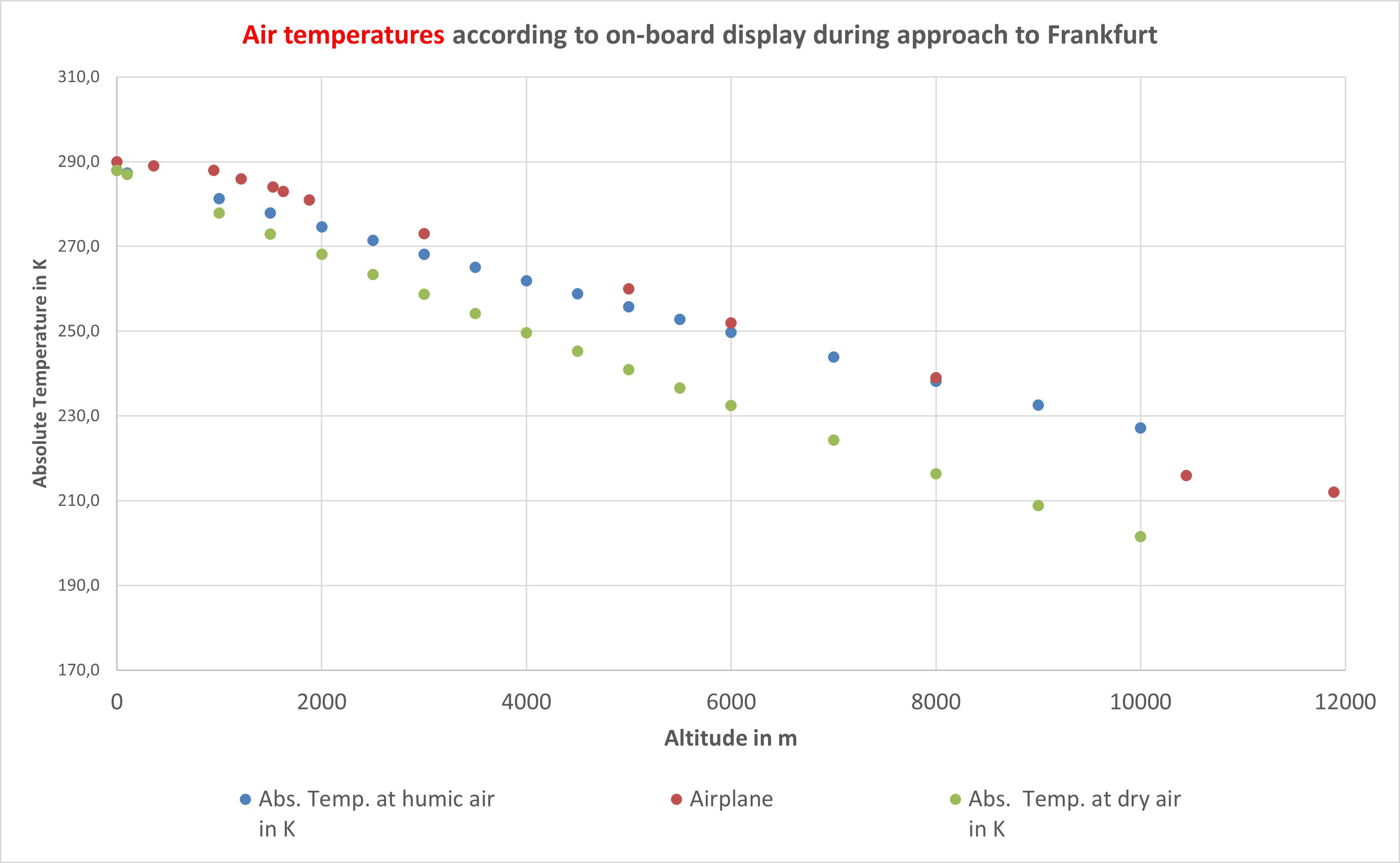

The temperature at an altitude of 5,400 m corresponds to the Earth’s average radiation temperature, or more precisely, the average temperature of the gaseous envelope surrounding the Earth, which is generally given as 255 K. This value corresponds to calculated values for humid air and largely agrees with observations, for example during the landing approach of an aircraft (see below).

© Brugger, 2023 |

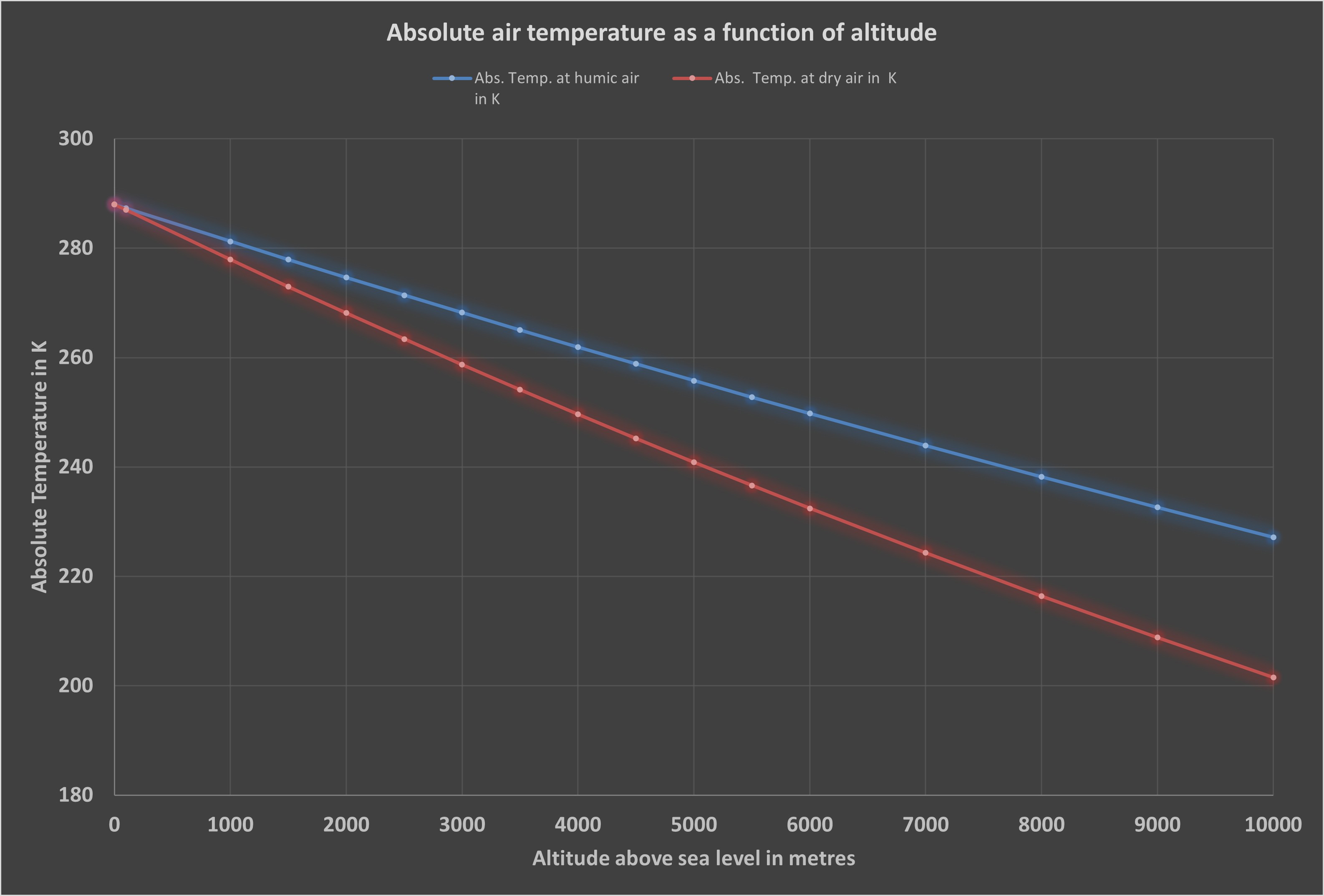

The strong influence of water vapour is also evident: humid air contains considerably more heat energy than dry air, which is why the temperature decreases less sharply with increasing altitude. The reason for this difference in behaviour is the latent heat stored in the water vapour.

The values displayed by the on-board system during an approach to Frankfurt Airport show that the theoretical calculation for air with normal humidity corresponds well with actual measurements. The ground temperature was about 5–8 K above the 15 °C (288 K) underlying the blue curve. At altitudes above 10,000 m, the measured temperatures also indicate significantly drier air.

Air temperature as a function of altitude |

Note:

The data and tables underlying the diagrams are available for direct download. Two curves were calculated for the air temperature: one for dry air (red line) with the isotropic exponent i = 0.286 and one for air with normal humidity (blue line) with i = 0.19.

In the second case, water vapour, which was not previously taken into account, is included. See also the page ‘The global water cycle’ in the article Wind – invisible, mysterious and full of energy.

Greenhouse effect and greenhouse gases?

How can the lower layer of the troposphere become warm and remain warm when temperatures of up to -80° C already prevail at an altitude of approximately 15 km and warm air masses are known to rise?

How can it be explained that the radiation temperature of the Earth is 255 K, but the average temperature on Earth is 288 K?

In response to these questions, “scientists(?)” invented the greenhouse theory and postulated that infrared radiation emitted by the Earth is absorbed in particular by CO2 and then radiated back to the Earth. Reliable physics was left out of the equation, opening the door to an unproven theory.

All we need to do is look at the physics.

As already explained above, the higher surface temperature of 288 K on Earth, in contrast to the average radiation temperature of 255 K, is due solely to the compression of air at normal humidity.

The average radiation temperature corresponds to the average temperature of the 50 % cold and 50 % warm air masses in the atmosphere.

Neither a greenhouse effect nor greenhouse gases are necessary to explain atmospheric temperatures! A theory derived from observations and based on presumed ‘key theoretical findings’ (IPCC) is and remains only an unproven hypothesis. And a hypothesis does not become true simply because many people believe in it.

It is undisputed that the main source of temperature on Earth or the Earth's surface is solar radiation. It is also undisputed that this has been the case for billions of years and that a wide variety of climatic scenarios have occurred on Earth completely without human intervention and in a natural way. These climatic changes were extreme in scale and have nothing in common with the comparatively marginal fluctuations or changes in temperatures in the zero decimal range, which are generally referred to today as climate change.

All gases in the open air envelope behave similarly and store heat energy. The specific heat capacity of air is essentially determined by nitrogen, oxygen and water vapour. The additional water vapour acts as the main energy carrier (humid air). The specific heat capacity indicates how much heat energy is required to increase the temperature of a substance with a mass of 1 kg by 1 Kelvin. In terms of mass, the specific heat capacity of water is about four times higher than that of air.

However, the density of air at 1.29 kg/m³ is considerably lower than that of water at 1,000 kg/m³. In terms of volume, water can therefore store several thousand times more energy than the same amount of air. Or conversely: small amounts of water vapour in air store enormous amounts of heat.

Air is also a very poor heat conductor, which is why warm air must be moved, e.g. by convection or wind. Increasing sealing of the landscape and, above all, open-space PV systems are causing standing air to heat up significantly, which is why wind is essential for a balanced climate. It is also known from hair dryers and fan heaters that air cools down very quickly, no matter how hot it is. Air is also highly transmitting of infrared radiation. If this were not the case, the sun's radiation would not reach the earth's surface.

Conclusion:

In summary, it can be said that the essential climatic events take place in the troposphere and here in the lowest altitude ranges of a few thousand metres above sea level (biosphere).

And this is precisely where humans intervene, extracting massive amounts of energy from the troposphere by means of wind turbines, on coasts, in wind corridors and on mountain ranges! The wind, together with water vapour and its distribution, is the essential climatic factor.

Further and more detailed information on the structure of the atmosphere, tropospheric weather cells (Hadley, Ferrel, Polar) and wind currents, as well as the global water cycle, can be found in the book Wind mania – Wind mania and its climatic consequences.

DE

DE  EN

EN