The gaseous envelope surrounding Earth is known as the atmosphere. Although humans are in constant contact with it, rely on it for respiration, and all phenomena directly relevant to life occur within only the lowest 1 to 1.5 per mille of its approximately 10,000-kilometer vertical extent, relatively few people have a precise understanding of what the atmosphere is, which physical and chemical processes occur within it, and what role it plays in regulating Earth’s climate and temperature.

This page presents a detailed description of the structure of the atmospheric gas envelope, while the page Air Pressure and Temperature addresses the associated climatic relationships.

How is the atmosphere structured?

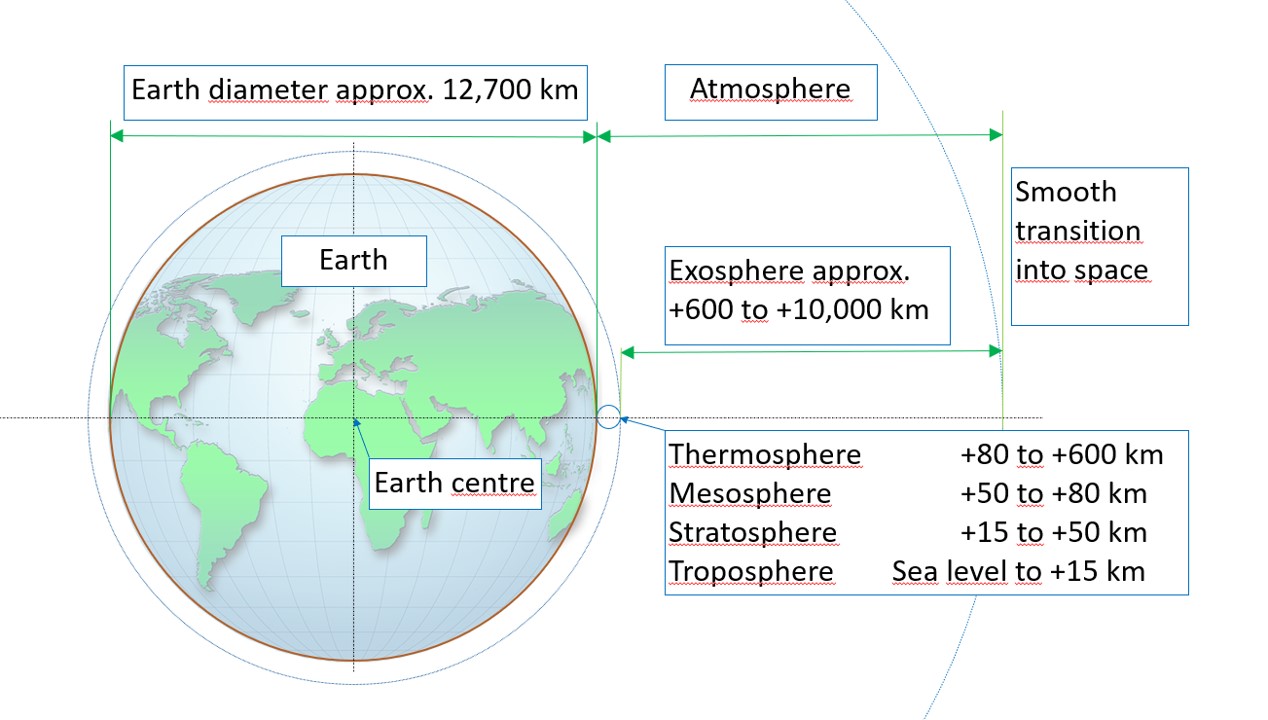

If you type “structure of the atmosphere” into an image search engine, you will quickly find countless illustrations. Most of them show the atmosphere divided into colourful layers, and they usually use a highly distorted scale. As a result, these images can give a misleading impression of what the atmosphere really looks like.

When the true proportions are taken into account, a very different picture of the atmosphere as a whole emerges:

(© Brugger, 2023) |

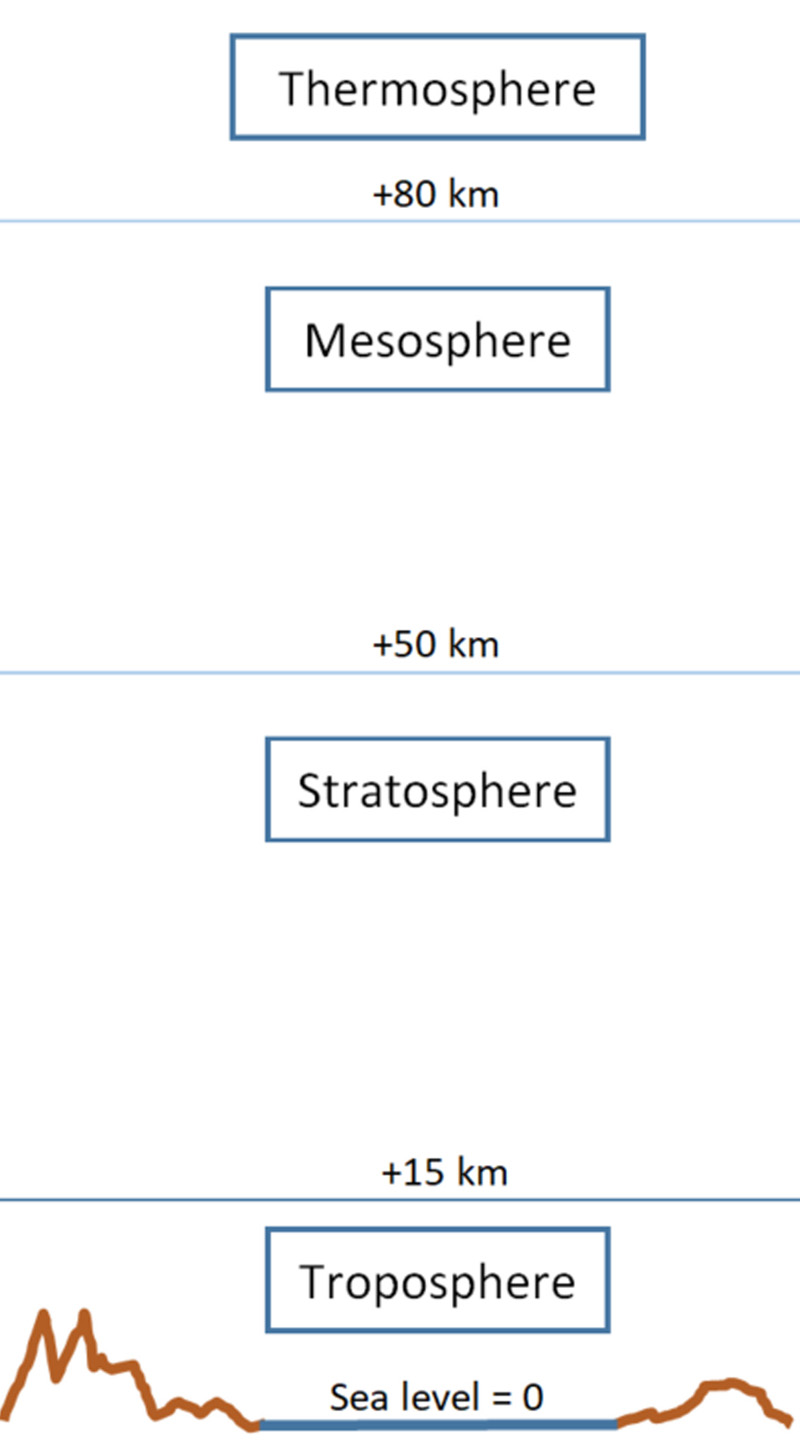

1. Troposphere

Although the troposphere is the thinnest atmospheric layer, extending from approximately 8 km at the poles to up to 15 km at the equator, it contains almost all atmospheric water vapor and about 85 % of the total air mass — a relationship that can be readily explained using the barometric height formula. It is the layer in which humans live and thus constitutes our immediate atmospheric habitat.

The troposphere receives its heat primarily from the Sun. With increasing altitude, air density and, consequently, temperature decrease (depending on humidity) at an average lapse rate of approximately 6.5 to 10 °C per 1,000 m, reaching values of about −80 °C at the tropopause. As a general rule, drier air exhibits a greater rate of cooling.

The planetary boundary layer of the troposphere, which is approximately 1.0 to 2.5 km thick and contains the most densely compressed air, together with the characteristics of Earth’s surface, exerts a strong influence on meteorological variables such as temperature, wind, humidity, and precipitation.

(© Brugger, 2023)

2. Stratosphere

The stratosphere, in which gas density is significantly lower, extends from approximately 15 km to about 50 km in altitude. Within this layer, an unusual temperature increase occurs, rising from around −80 °C at the tropopause (the lower boundary) to approximately 0 °C (273 K) at the stratopause (the upper boundary).

High-energy UVC radiation (100–280 nm) splits oxygen molecules (O₂) in the air. The resulting oxygen atoms then combine with other oxygen molecules to form unstable ozone molecules (O₃). In the resulting layer, known as the ozone layer, a large portion of the Sun’s intense ultraviolet radiation is absorbed and converted into kinetic energy and heat. This process protects our habitat in the troposphere from excessive and harmful UV radiation.

In addition to the temperature inversion, the ozone layer exhibits a second atmospheric anomaly. Ozone is approximately one-third heavier than oxygen and, with a density of about 2.15 kg/m³, significantly denser than air, which has a density of roughly 1.29 kg/m³. In theory, ozone should therefore sink under Earth’s gravity; however, this does not occur. The reason for this anomalous behavior lies in the temperature increase caused by the absorption of high-energy UVC radiation by ozone molecules. This radiation raises the internal energy, and thus the temperature, by exciting molecular vibrational and rotational modes before the energy is re-emitted as electromagnetic radiation.

When these processes are taken into account, ozone transitions from acting as a greenhouse gas to functioning as a protective gas—at least within the stratosphere. Further details are provided in the section Ozone Layer.

3. Mesosphere

The mesosphere extends from approximately 50 to 80 km above sea level. Within this layer, gas density continues to decrease and is only about one-tenth of one percent of the air density at sea level. Nevertheless, this low density is sufficient to cause small meteorites entering Earth’s gravitational field at high velocity to burn up due to friction, appearing as shooting stars.

Temperatures in the upper regions of the mesosphere can drop to as low as −100 °C, making it the coldest layer of the entire atmosphere.

4. Thermosphere

Above the mesosphere lies the thermosphere, which extends from approximately 80 km to about 600 km above Earth’s surface. Within this layer, air density continues to decrease and becomes extremely low, while theoretical temperatures range from about 300 °C at night to approximately 1,500 °C during the day—values comparable to those found in the exosphere.

Geostationary satellites and the International Space Station (ISS) orbit Earth within this region.

5. Exosphere

The exosphere is the outermost and most spatially extensive layer of the atmosphere. It begins at an altitude of approximately 600 kilometres and extends to around 10,000 kilometres, where it gradually merges into interstellar space. In this region, almost all gas molecules are ionised. The gas density is extremely low, and the few remaining particles move at high speeds and are separated by great distances.

In theory, temperatures well above 1,000 °C would prevail here, but only if there were enough matter to absorb electromagnetic radiation and convert it into heat. Thus, although the exosphere by far represents the largest portion of the atmosphere by volume, it contains only a tiny fraction of the total atmospheric gas mass.

What does atmospheric air consist of?

The entire atmosphere is a continuous mixture of gases that is held close to Earth by gravity and becomes progressively less dense with increasing altitude. The atmospheric spheres described above serve only to define spatial regions; they are not separate physical boundaries.

The main components of atmospheric air are:

-

nitrogen (78%

-

oxygen (20.8%),

-

trace gases such as the noble gas argon, methane, and ozone (1.16%) and carbon dioxide (0.04%),

-

and water vapour (humidity), which varies in concentration.

Conclusion:

In summary, it can be stated that the atmosphere

- is an open gaseous envelope (and not a greenhouse),

- the primary climatic processes occur in the lowest part of the troposphere,

- particularly within the planetary boundary layer at altitudes of up to a few thousand meters above sea level, where the biosphere is located.

Temperature generally decreases with increasing altitude. The underlying physical relationships are explained on the following page Air Pressure and Temperature.

Further and more detailed information on the structure of the atmosphere, tropospheric weather cells (Hadley, Ferrel, Polar) and wind currents, as well as the global water cycle, can be found in the book

Wind Mania – The Wind mania and its climatic consequences.

DE

DE  EN

EN